Energy Metabolism Explained: How Your Body Powers Movement and Recovery

Energy Metabolism Explained: How Your Body Powers Movement and Recovery

What Is Energy Metabolism and Why Does It Matter for Fitness?

Think of energy metabolism as your body's power grid. It's converting breakfast into bench press reps, lunch into a 5K run, dinner into muscle repair while you sleep. More precisely, it's the chemical process that transforms calories from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—the only energy currency your cells actually accept.

Here's why this matters beyond biochemistry class: A sprinter who understands why their quads scream after 30 seconds can adjust their interval timing to maximize recovery. An ultramarathoner who knows their fuel tank switches around mile 18 can plan nutrition to avoid bonking. Without this foundation, you're guessing. With it, you're engineering results.

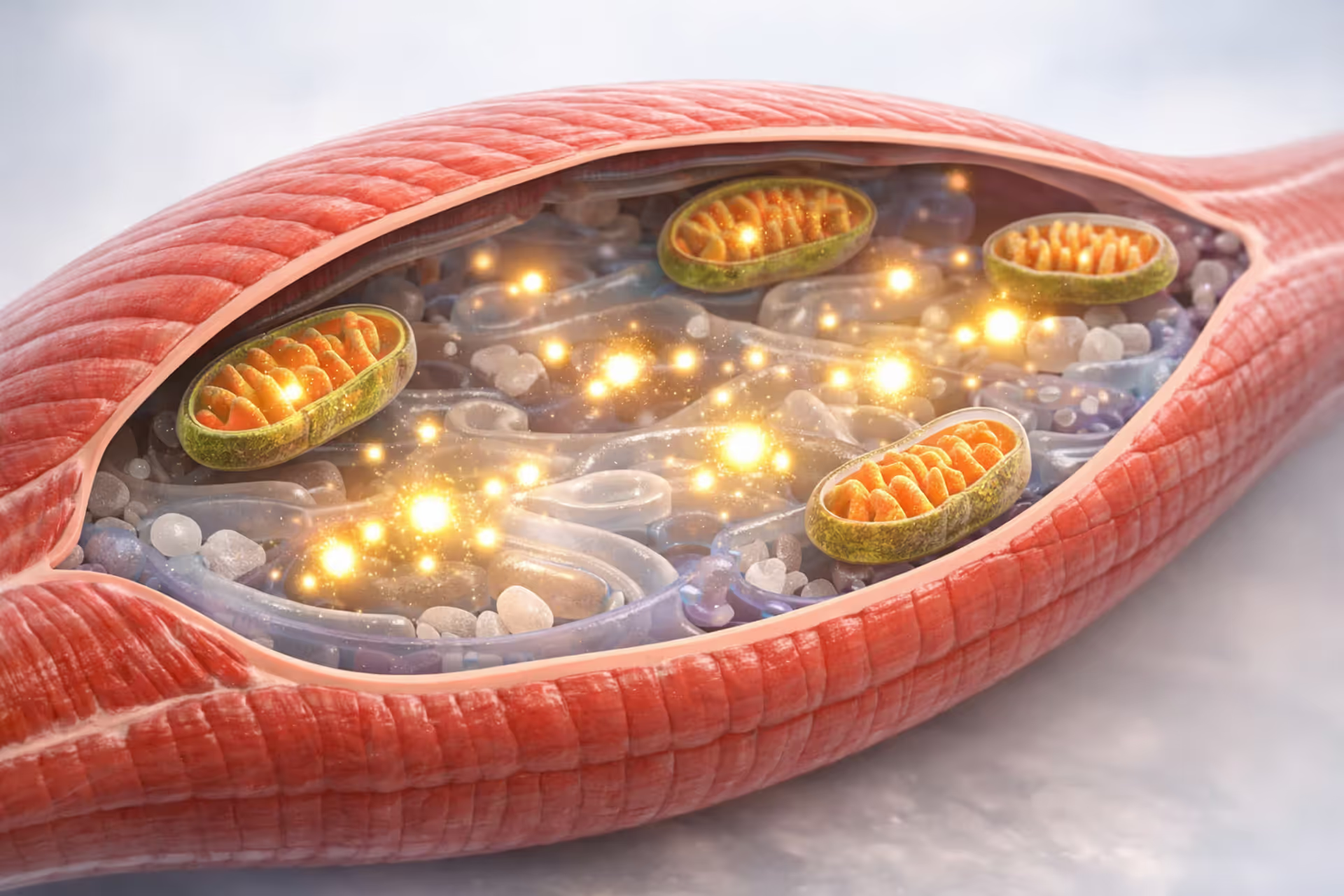

Your cells manufacture ATP through cellular respiration, mostly inside mitochondria (though some reactions kick off in the cytoplasm first). Which pathway dominates depends on three factors: how hard you're working, what fuel's available, and whether oxygen supply keeps pace with demand. Your body never completely shuts off one system to activate another—they're all running simultaneously, just contributing different percentages based on what you're demanding right now.

One more thing: storing ATP directly doesn't work well. Your muscles hold maybe 2-3 seconds worth at any moment. Everything beyond that requires real-time manufacturing, which is where things get interesting.

Author: Caleb Foster;

Source: thelifelongadventures.com

The Three ATP Energy Systems Your Body Use During Exercise

Your muscles can't stockpile much ATP. Once you burn through those first couple seconds, you need regeneration systems that work at vastly different speeds and capacities.

The Phosphagen System (Immediate Energy)

Muscle cells store phosphocreatine—essentially a rapid-response ATP battery. An enzyme called creatine kinase strips a phosphate group off phosphocreatine and slaps it onto ADP, instantly rebuilding ATP. No oxygen required. No glucose breakdown needed.

This system peaks during the first 10 seconds of all-out effort. Picture a vertical jump, the first three reps of a max-effort deadlift set, a 40-yard dash. By 30 seconds into a maximal sprint, phosphocreatine stores drop to roughly half. Power output craters accordingly.

Recovery between efforts becomes critical here. Three to five minutes of rest restores about 95% of phosphocreatine. Give yourself only 30 seconds? You'll barely hit 50% restoration. Watch powerlifters at a meet—they're not scrolling their phones for five minutes between attempts because they're lazy. They're waiting for biochemistry to complete.

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

— George E. P. Box

The Glycolytic System (Short-Term Power)

Once phosphocreatine tanks but you're still pushing hard, glycolysis takes over. Your body rips glucose or stored glycogen apart into pyruvate molecules, cranking out ATP without needing oxygen present. Fast, but wildly inefficient—you get just 2 ATP per glucose molecule this way, versus 30-32 when oxygen's available.

Glycolysis dominates during efforts lasting 30 seconds to maybe 2 minutes. A 400-meter sprint. That brutal CrossFit workout with minimal rest. Leg press sets of 15-20 reps approaching failure. The ceiling isn't running out of glycogen (you've got enough stored for hours of moderate work). It's the hydrogen ions piling up faster than your body can buffer them, interfering with muscle contraction. That burning sensation during a hard set? Metabolic acidosis courtesy of rapid glycolysis.

The Oxidative System (Long-Duration Fuel)

Author: Caleb Foster;

Source: thelifelongadventures.com

When oxygen delivery matches oxygen demand, your mitochondria shift into high gear. Pyruvate gets processed through the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain—an elegant system producing ATP much slower than the other pathways but vastly more efficiently. You'll squeeze 30-32 ATP from each glucose molecule. A single palmitate molecule from fat breakdown yields 106 ATP.

This system powers everything lasting beyond a few minutes at low to moderate intensity. Distance running, cycling centuries, swimming miles, even walking your dog. Fat becomes increasingly important as duration extends, sparing precious glycogen. Elite endurance athletes develop ridiculous mitochondrial density through years of training—picture more power plants per muscle cell, plus the vascular network to fuel them.

Aerobic vs Anaerobic Energy: Key Differences That Impact Your Workouts

The oxygen-dependent versus oxygen-independent split shapes every training decision you'll make. Aerobic metabolism needs oxygen to completely oxidize fuel inside mitochondria, producing carbon dioxide and water. Clean byproducts, sustainable for hours. Anaerobic pathways (phosphagen and glycolytic) operate when oxygen's scarce or you're moving too fast for complete oxidation, generating ATP rapidly but accumulating metabolites that force you to stop or slow down.

Intensity dictates the blend. Below roughly 60-70% of max heart rate, oxidative metabolism handles almost everything. Push above lactate threshold (around 80-90% max for most people), and glycolysis floods your muscles with lactate and hydrogen ions faster than you can clear them. The phosphagen system only contributes substantially during the opening seconds of maximal efforts or when you superimpose explosive movements onto steady work—like surging during a race.

Recovery timelines reflect these metabolic differences. Phosphocreatine resynthesis needs only ATP and completes within minutes. Clearing lactate and restoring muscle pH takes 30-60 minutes. Fully restocking glycogen after serious depletion? You're looking at 24-48 hours plus deliberate carbohydrate intake. Programs that ignore these windows stack fatigue on top of fatigue until adaptation stalls.

| Feature | Aerobic Metabolism | Anaerobic Metabolism |

| Oxygen requirement | Must have oxygen present | Works fine without oxygen |

| Duration of activity | Sustained work beyond 2-3 minutes | Brief, explosive efforts under 2 minutes |

| Exercise intensity | Low to moderate (conversational pace) | High to absolute max (can't sustain long) |

| Primary fuel source | Fats and carbohydrates together | Phosphocreatine first, then glucose/glycogen |

| Byproducts | Carbon dioxide and water | Lactate, hydrogen ions, considerable heat |

| Recovery time | Minimal between bouts | Ranges from 30 seconds to multiple days |

| Training examples | Long runs, zone 2 cycling, easy swimming | Max lifts, track sprints, HIIT intervals |

| Fatigue mechanism | Fuel depletion, overheating | Metabolite buildup, dropping pH |

Author: Caleb Foster;

Source: thelifelongadventures.com

How Metabolic Pathways Convert Food Into Usable Energy

The journey from chicken breast or sweet potato to muscular contraction involves multiple interconnected pathways. Each contributes based on what substrate's available and what your cells need right now.

Glycolysis: Breaking Down Carbohydrates

Glucose entering muscle tissue gets processed through glycolysis right in the cytoplasm. Enzymes break the six-carbon molecule into two three-carbon pyruvate molecules. The reaction actually costs 2 ATP upfront but generates 4 ATP, netting 2 ATP per glucose. When oxygen's scarce or energy demand exceeds what mitochondria can handle, pyruvate converts to lactate. This regenerates NAD⁺, a coenzyme required for glycolysis to continue running.

Lactate isn't waste—that's outdated thinking. It shuttles to your liver where gluconeogenesis rebuilds it into glucose (the Cori cycle). Less-active muscles and cardiac tissue can oxidize it directly for fuel. Well-trained athletes produce plenty of lactate during hard efforts but clear it much faster than untrained folks, which raises lactate threshold and allows harder sustainable paces.

The Krebs Cycle and Electron Transport Chain

With adequate oxygen, pyruvate enters mitochondria and feeds into the Krebs cycle (some people call it the citric acid cycle or TCA cycle). The cycle itself only directly produces 2 ATP per glucose—not much—but it generates high-energy electron carriers called NADH and FADH₂. These molecules power the real money-maker: the electron transport chain.

The electron transport chain sits embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. It uses electrons from NADH and FADH₂ to pump protons across the membrane, building up an electrochemical gradient. When protons flow back through ATP synthase (like water through a turbine), they drive ATP production—roughly 26-28 additional ATP per glucose. This explains why aerobic metabolism is so efficient compared to glycolysis alone: complete oxidation yields 15-16 times more ATP.

Fat and Protein Oxidation Pathways

Fat breakdown starts with lipolysis. Hormones like epinephrine trigger the release of fatty acids from stored triglycerides. These fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation inside mitochondria, where enzymes cleave two-carbon units that enter the Krebs cycle as acetyl-CoA. A 16-carbon palmitate molecule generates 106 ATP—tremendous energy density, though requiring more oxygen per ATP than carbohydrate.

Fat dominates fuel provision during low-intensity long efforts and between meals. But there's a catch: fat oxidation slows dramatically without adequate carbohydrate availability. The Krebs cycle needs intermediates that come from carbohydrate metabolism to run efficiently. This interdependence explains why extreme low-carb diets often hammer high-intensity performance even when fat stores are abundant.

Protein contributes minimally during most exercise—typically under 5-10% of total energy except during prolonged fasting or ultra-endurance events exceeding several hours. Amino acids can be deaminated and converted into Krebs cycle intermediates, but this process is metabolically expensive. Your body reserves it for emergencies, not routine fuel provision.

Practical Applications: Matching Energy Systems to Your Training Goals

Author: Caleb Foster;

Source: thelifelongadventures.com

Smart programming targets specific pathways based on what you're trying to accomplish. Each system adapts to training stress, but those adaptations are highly specific—train the phosphagen system, and your oxidative capacity won't improve much.

Developing the phosphagen system requires maximal or near-maximal efforts lasting 5-10 seconds with complete recovery. Olympic lifts, box jumps, short sprints. Rest 3-5 minutes between sets to allow full phosphocreatine restoration. Cutting rest to save time defeats the purpose—you'll just train glycolytic capacity instead. Creatine monohydrate supplementation (3-5g daily) can boost phosphocreatine stores 10-40%, especially benefiting people who start with lower baseline levels (often those eating little red meat).

Building glycolytic capacity needs repeated high-intensity intervals that accumulate serious metabolic stress. Try 6-10 × 400 meters with 2-3 minute recoveries, or 4-6 sets of 60-90 second efforts at 90-95% max heart rate. These sessions are brutally taxing and require 48-72 hours for complete recovery. Program them more than twice weekly and you're flirting with overtraining while getting diminishing returns.

Expanding oxidative capacity requires sustained aerobic work stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and capillary development. Long steady runs or rides at 60-75% max heart rate, tempo efforts at lactate threshold, even high-volume resistance training with abbreviated rest can drive these adaptations. Consistency trumps intensity here—three to five aerobic sessions weekly produce better results than sporadic heroic efforts followed by couch time.

Effective periodization integrates these approaches across training cycles. A strength athlete might emphasize the phosphagen system during power phases, add glycolytic work during hypertrophy blocks, maintain baseline aerobic fitness year-round. An endurance athlete builds an aerobic base over months, then layers in lactate threshold and VO₂ max intervals as competition approaches, preserving some explosive work to maintain neuromuscular qualities.

Common Mistakes That Sabotage Your Metabolic Efficiency

Too many athletes train in what I call the "gray zone"—working too hard to build aerobic capacity effectively but not hard enough to stress glycolytic pathways meaningfully. This moderate-intensity trap generates fatigue without driving clear adaptations. Easy days should be truly easy (you could hold a conversation). Hard days should be genuinely hard (talking becomes impossible during work intervals). The middle ground is mostly just accumulated junk mileage.

The dose makes the poison.

— Paracelsus

Scheduling high-intensity sessions too close together prevents full glycogen restoration and metabolic recovery. Back-to-back interval workouts, or even spacing them just 24 hours apart, means starting the second session with depleted substrates and accumulated fatigue. Both quality and adaptation suffer. You'd get more from one high-quality session than two mediocre ones.

Poor nutrition timing undermines specific adaptations. Training fasted can enhance fat oxidation capacity for aerobic work. But attempting high-intensity glycolytic intervals without adequate carbohydrate availability? You'll struggle through the session and recover poorly afterward. Consuming 30-60g of carbs within 30 minutes post-workout maximizes glycogen resynthesis rates—timing actually matters here, unlike the overblown "anabolic window" for protein.

Fuel availability mismatches create frustrating limitations. Athletes following very low-carb approaches often hit walls during high-intensity work because glycolytic flux fundamentally requires glucose. Conversely, training exclusively at high intensity without developing fat oxidation leaves you vulnerable during long events when glycogen inevitably depletes regardless of fitness level.

Misunderstanding intensity zones produces ineffective training distribution. Heart rate monitors help, but most people misjudge their actual intensity. "Moderate" often creeps into "moderately hard." Lactate threshold testing, the talk test, or power meter data provide more accurate guidance, ensuring you're genuinely training the intended energy system rather than just accumulating fatigue.

Frequently Asked Questions About Exercise Metabolism

Understanding energy metabolism converts guesswork into precision. When you recognize that a 10-second sprint depletes phosphocreatine, a 400-meter effort taxes glycolytic capacity, and a 10K depends on oxidative efficiency, you can design workouts targeting specific adaptations instead of hoping random hard work produces results.

The interplay between ATP systems, substrate availability, and recovery requirements creates complexity. But it's navigable complexity. Training one system exclusively leaves metabolic gaps in your capabilities. Attempting to hammer all systems simultaneously produces mediocre adaptations across the board plus chronic fatigue. Periodization, intelligent intensity distribution, and nutrition timing aligned with energy system goals create conditions for meaningful progress.

Your body already possesses remarkable metabolic machinery. Understanding its operation gives you the knowledge to stress these systems appropriately, recover adequately, and adapt progressively toward whatever performance objectives you've set. The biochemistry might seem abstract, but its applications are concrete and immediately useful.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on this website is provided for general informational and educational purposes related to health, yoga, fitness, and overall wellness. It is not intended to replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

All information, workout suggestions, yoga practices, nutrition tips, and wellness guidance shared on this site are for general reference only. Individual health conditions, fitness levels, and medical needs vary, and results may differ from person to person. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before starting any new exercise program, dietary plan, or wellness routine.

We are not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any outcomes resulting from the use of information presented on this website. Your health and fitness decisions should always be made in consultation with appropriate medical and fitness professionals.